Algorithm Aversion

Imagine you’re at a medical appointment with a choice of doctor: a human doctor, or an AI-powered machine. Which would you choose?

Obviously, not just any human. An above average, nice enough, passed all their studies, decent hygiene, had a good night’s sleep and back from a light lunch human. And obviously, not just any machine. A robot dedicated to all medical knowledge, trained on your personal medical history, and complete with a non-creepy robot smile.

How you feel about these two options reflects two common psychological traits: Algorithm Aversion and Automation Bias.

Algorithm Aversion is when we don’t trust machines, even when they outperform humans. Some people will prefer just having a human behind the wheel, even if a self-driving car will be statistically safer.

We’re less accepting of machine mistakes - perhaps one reason for this is we don’t expect them to learn and improve, so a mistake is seen as an eternal and irredeemable one? If AI can learn and self-improve, this aspect may disappear altogether.

Automation Bias, on the other hand, is when humans tend to favour suggestions from automated decision-making systems. People see technology as less errorful, or more objective than humans.

This isn’t a right or a wrong, these are just traits. But both of these may have pitfalls or even be a new fault line for polarisation in future.

To a certain extent, we have been conditioned to expect correctness from machines. Given a massive multiplication (say 81924 * 17738293 for example), most would choose a calculator over a mathematician - well, probably the calculator on their iPhone… when was the last time you saw a standalone calculator!?

In fact, even if a mathematician gave you an answer, you’d probably want to check their work with a calculator anyway. Just to be sure. In this way, everyone has a little automation bias for narrow expertise.

But, when a machine gives an incorrect answer, it tends to really rattle our cages (no “AI will enslave us all” pun intended). If a calculator ever gave you the wrong answer, you’d throw it out (as long as it wasn’t your iPhone). Maybe this is why some are so dismissive of Large Language Models (LLMs) like ChatGPT - they break the social-digital contract of trusting machines to give us correct information.

LLMs don’t try to be correct (although they aren’t opposed to it). They try to be plausible. They attempt to say “what is the best thing I could say here that sounds correct”. Notice “sounds” and “is” are 2 different things. Hallucinations are the term given to when LLMs just completely make things up, like sounding confident giving you a link to a scientific article that doesn’t exist. They are statistically choosing what would be most plausible for you, and using it - somewhat untethered by reality. Sometimes, you could describe this as creativity. An AI’s hypothetical cure for a disease, though citing non-existent papers, could inspire real scientific inquiry. Some teams are even developing AI scientists capable of generating and testing these hallucinated hypotheses.

LLMs currently break our previous expectations of computers. We expect more database lookups than creative expression from our machines. Will that change?

Microsoft and GitHub’s Co-pilots are perfectly named to set the scene for their use. LLMs cannot be trusted, but they can help. A pilot always has the responsibility for the plane, whether the auto-pilot is engaged or not. When working with AI, you are the pilot. You have to take responsibility for the work. You can’t blame the AI.

Many people using LLMs habitually - becoming accustomed to their power and their inaccuracies. Will this exposure over time change our behaviour, guiding AI through hallucinations rather than thinking it’s broken? Will the 79% of teenagers who use GenerativeAI tools like ChatGPT just see it as normal to patiently guide, encourage, and explain to a machine.

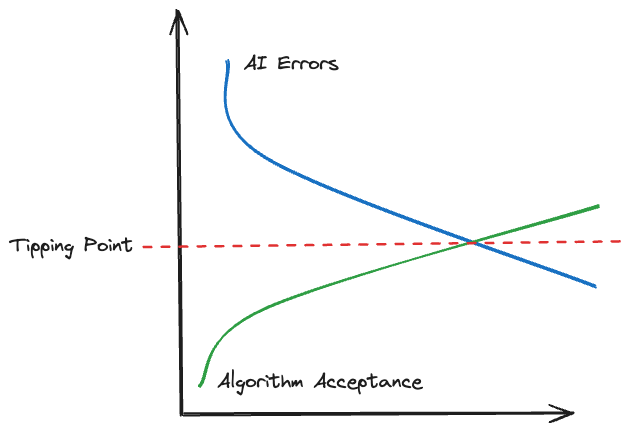

And as the population may grow to expect and embrace inaccurate machine responses, and it may become more natural to converse and iron out those creases as they arise, so too will machines become more accurate. Errors will be engineered out gradually, trending towards zero.

There’s a natural tipping point: as humans become more accepting of machine errors, and engineering means AI error rates trend to zero, there’s a point which AI potentially accepted as standard in most situations.

At that point, the gate adoption of AI in many domains is likely to be wide open! If the error rate is 0, then that’s a given. If people accept large error rates, the same. But the trends seem to indicate that even if those two extremes don’t occur, we will see a societal change in attitudes towards computers and AI, and what that means will be interesting to see.